GONE FISHIN'

Early

one Saturday morning when I was about ten, Father gently nudged me from a deep

slumber. “Time to go fishin’, Sweetie.” Reluctantly I uncovered my face; blinked;

closed my eyes; and blinked again. I sat

up, stretched my arms above my head; and yawned, remembering how I’d pleaded

with him the night before.

“May I

go with you, pleeeease Daddy?” I begged.

Taking

me wasn’t easy, for I was squeamish around worms and water. But I’d tolerate almost anything just to have

some alone time with Father.

“But

Daddy, it’s dark outside. Aren’t the

fish sleeping?”

“They’ll

be awake soon enough. Get a move on!”

He

loaded me and his fishing gear into his pickup truck and drove to nearby Lake

Lavon where—at the crack of dawn—he launched his flat bottom boat, the

Nini-Poo, into the water. It was a

sultry, windless August morning; and the lake—flat as any mirror—lay before us

without a single ripple as if time itself had been frozen. From

the tall pines around the edge came not a sound, no movement of branches and no

birds calling.

Father

tugged on the choke of his outboard motor and pulled on the starter rope three

times before the engine sputtered into action.

We skittered across the lake, shattering the lake’s glassy appearance. Once we reached an isolated cove, Father

turned off the ignition, letting the boat come to a gentle stop. He reached under his seat; fetched his bucket

of worms; nabbed one of the larger ones; and drove the hook into the thicker

end. He cast my live worm into the water

and handed me my cane pole.

“Watch

the bobber,” he said, his finger pointing to the water. “When a fish nibbles, let him have a taste,

then pull.”

“Okay

Daddy. I will.”

He baited

his own hook and cast his line into the water; we sat and fished for hours. From the pine trees around the lake’s edge

came nary a sound—only the sound of my father’s breathing. For a moment I forgot to watch my pole. The end splattered into the water, sending

dragonflies off their lily pads. “Whoa,

watch your fishing pole!” he said, reaching over to steady the cane pole.

Father

sat as still as the pines, as if time were suspended and our minutes were as

countless as summer strawberries. “Daddy,”

I rested my cheek against his arm, “are you SURE there’s fish in this cove?” He

chuckled and kissed me on the cheek.

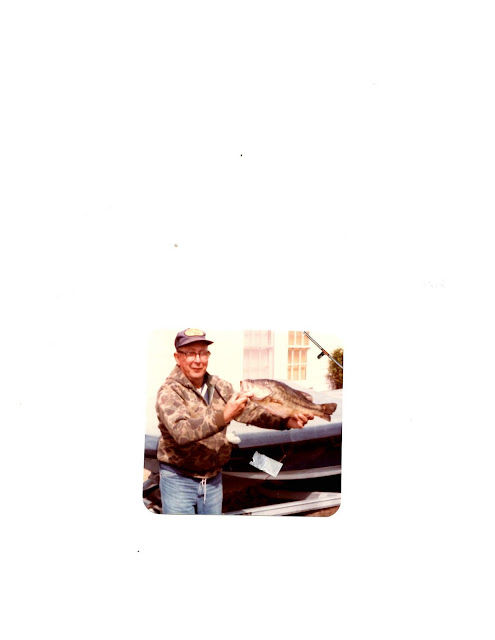

Suddenly, the bobber zinged under the

water. “It’s a whopper!” he cried. I leaned back into his arms; we pulled

together. Breaking through the water,

erupting

erupting

into the glimmer of the morning light, burst the biggest fish I’d ever

seen. Father unhooked the shimmering

fish. I held my breath, and Father

beamed. Neither of us spoke; we just

stared at one another. The gift of that day

spent with Father was one of the best presents I ever got.

Comments

Post a Comment